Two walks at Black Mountain*; two themes. One, a 360˚ view of the “bush capital”. Two, the multitude of shapes and textures among trees.

One: 360˚

Loop around the summit of Black Mountain and the city, suburbs, paddocks and mountains are revealed by turns through the trees. Many of the trees are fuzzy with new growth, emerged since they were thoroughly defoliated in the January hailstorm.

On the first day, the lake, glimpsed in patches through the trees, is sunlit and reflective; the southern suburbs an intricate pattern of deciduous colour and eucalypt green. A few days later, on my second walk beneath patchy clouds and wind, the lake is dark, navy and rippling.

One: the lake reflective through the trees.

Walking clockwise, there is the brilliant green of the Arboretum and Mt Painter after the autumn rains. The unexpected high rise of Belconnen, half-hiding a silver patch of Lake Ginninderra. Suburbs and bush alternating across the northern suburbs.

Mt Majura to the north east; our place half way between. Then the surprising thickness, heaviness, of Civic with ANU in the foreground: I hadn’t quite realised the denseness of Canberra’s concrete centre.

Canberra is, architecturally, dominated by concrete: the stripped classical and brutalist shapes of the NLA and NGV; the landmark of Telstra tower; the leaden impression I have of the city centre.

The base of Telstra Tower at the top of Black Mountain.

This awareness of concrete it is one of the downsides of a city so interspersed with the bush: from within each patch of remnant vegetation, you emerge to a view of the built environment, a constant reminder of the encroachment of urbanity on nature, even as you appreciate the presence of nature within the urban.

Two: texture of the trees

On my second walk, I’m alone late on a cold, windy day. I walk up Black Mountain from behind the Botanic Gardens, a climb of nearly 200m to the summit. I often walk to think, but on this day I can’t seem to think: climbing the ridge, in the grey of the late afternoon, I can see only trees, endlessly interesting – a variety of shapes and forms within one species; I can hear only the distant hum of traffic.

Helpfully, interpretive signs give me the names of the main tree species on this part of the mountain:

Inland scribbly gum – Eucalyptus rossii

Inland scribbly gum – Eucalyptus rossii- Red stringybark – Eucalyptus macrorhyncha

- Cherry ballart – Exocarpos cupressiformis

- Red box – Eucalyptus polyanthemos

… And before I’ve gone ten steps I spot a scribbly gum. Briefly, before my eyes adjust, I think of graffiti. But these marks are left by moth larvae, boring a tunnel beneath the outer layer of bark, “first in long irregular loops and later in a more regular zigzag which is doubled up after a narrow turning loop” (CSIROpedia, 2015).

The moths are tunnelling through the cork cambium, the layer of tissue that produces tough protective cork. Their return journey is fascinating: the cork cambium produces scar tissue to fill the larval tunnel created by the caterpillar’s outward journey; when the caterpillar turns around, it retraces its route, devouring the nutritious scar tissue cells, quickly growing to maturity. The caterpillar leaves the tree, and shortly afterwards the outer bark comes away and the scribbles are exposed. (See Ecos Magazine for a more detailed explanation.)

I love that the CSIROpedia page where I found this information also contains a few lines from a Judith Wright poem, which I reproduce here:

The gum-tree stands by the spring.

I peeled its splitting bark

and found the written track

of a life I could not read.

– From A Human Pattern: Selected Poems by Judith Wright

When the scribbly gum sheds its bark annually, the journeys of that season’s moth larvae are revealed; changing the appearance of the tree year to year (Australian National Botanic Gardens, 2015).

Here, a red stringybark alongside a scribbly gum.

And a cherry ballart (Exocarpos cupressiformis). I read that these were used as Christmas trees in the early days of European colonisation, because of the cypress-like shape and look. But they are part of the sandalwood family, and are hemiparasitic on the roots of other trees, especially eucalypts.

after

I was thinking as I walked about the ugliness of the surfaces humans create from pourable substances: specifically concrete and asphalt. Today I read a 2019 Guardian article on concrete as “the most destructive material on earth”, contributing enough carbon dioxide to the atmosphere that, if it were a country, it would rank third in the world for emissions. Concrete suffocates soil, swamps and streams all over the planet. Sullivan’s Creek, which I walk along every day, is a prime example: there is no “creek” that I can see left in that concrete drain.

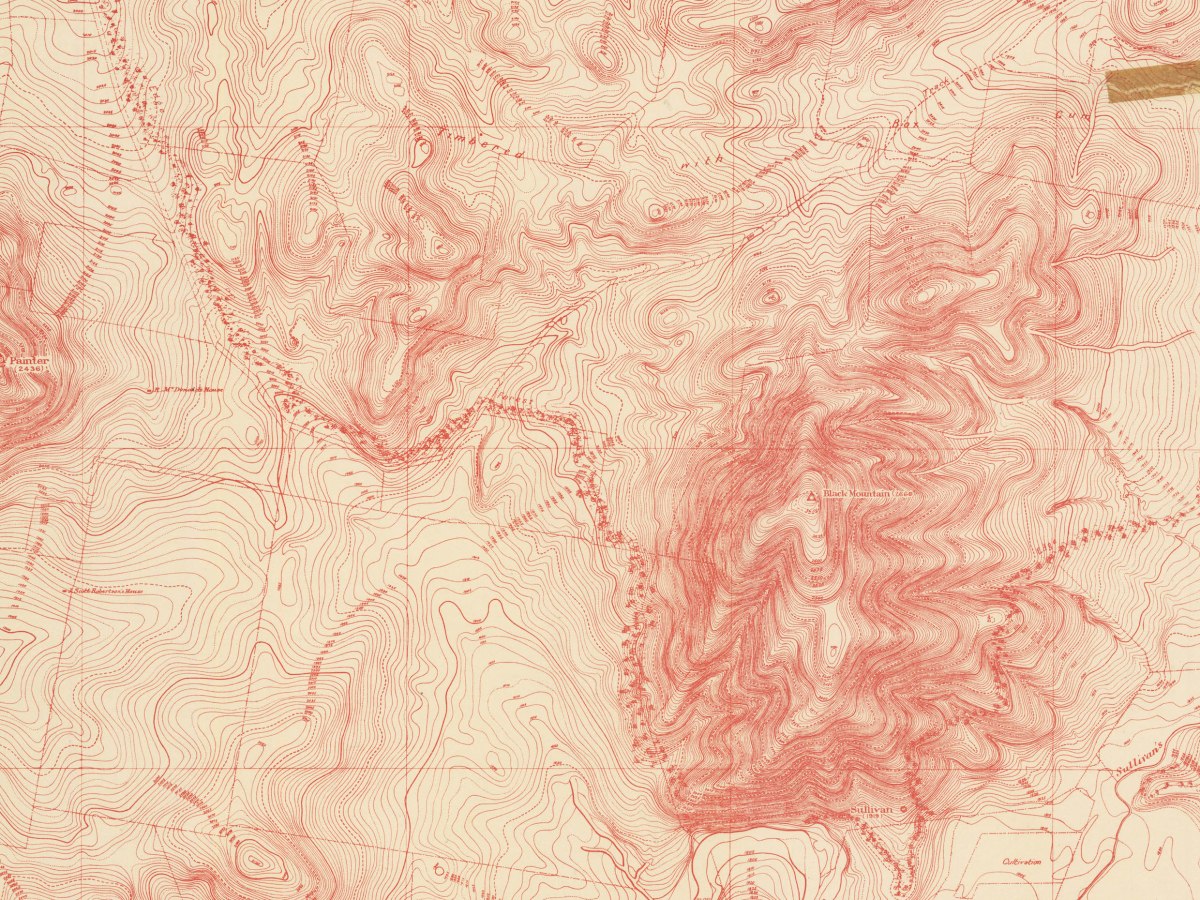

Delving into the ANU Asia-Pacific map collection, I found a map of Canberra from a time before concrete was dominant; from a time before the lake, when Black Mountain Peninsula was a spur and when Lake Burley Griffen was the Molongolo River.

This old topographic map creates, just briefly, a shift in perspective. From on-ground to birds-eye. Hidden gullies suggested in red lines on cream. The way vegetation can mask the contours of the ground.

From The Federal Capital Territory, Contour Map of the City Site and Adjacent Lands, Sheet 1, 1914, 1:9 600

See the full 1914 map, complete with tape holding it together, and the fascinating ANU collection of maps here.

* Using European names for landscape features like the mountains without providing an Indigenous name isn’t ideal, but I have had trouble finding agreed alternative names for Black Mountain and other prominent landmarks in Canberra.